CAVA

This piece is part of our series on Penedès, one of the great wine regions of Spain. We visited in July 2019.

All respect to France, but we have never tasted a Champagne as mindblowing as this Cava. Which one is it? Read on to find out!

You’ve probably seen Cava in the grocery store, and the ones we can find in the U.S. taste more or less as good as other low-priced sparkling wines.

We don’t tend to think of Cava when we think of high-end sparkling wine.

That’s going to change.

In this piece we plan to answer:

What grapes are used in Cava?

How is Cava made?

How is quality judged?

What is the biggest challenge for Cava makers?

What is Cava’s history?

How amazing can Cava be? (What is that fantastic looking wine in this photo at the top of this post?)

WHAT GRAPES ARE USED IN CAVA?

Champagne uses some combination of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier (yep, two of those are red grapes). Not all three are always used. Like Champagne, Cava tends to be made from three grapes, but they are all white.

XAREL●LO, MACABEU, PARELLADA

Xarel●lo, the dominant grape of Penedès, is often seen as the Chardonnay of the area and offers great fullness and body. Yes, its proper spelling includes the bullet between the two Ls.

Macabeu provides the freshness and acidity need to lift the wine with brightness

Parellada brings added fragrance and finesse

There are other grapes that can be used in Cava wines—the rules here are (2020) looser than in other wine regions—but the ones above are the dominant three. Chardonnay is also planted and used to provide roundness to the mouthfeel, but there is heated debate over its use. Traditionalists feel it detracts from the authenticity of a Spanish wine since the grape is French, and modernists advocate for it since the grape is widely known internationally and gives more recognition to the blend if included in the blend.

My vote is to stay with the true blend of Spanish tradition. (So is Jake’s.)

Enjoy learning how to pronounce the names of these Catalunyan grapes in our video introduction of Penedès. Also, enjoy Jake’s photography of the gorgeous Penedès vineyards we visited.

HOW IS CAVA MADE?

Cava wines are made with the same care and precision as French wines.

Sparkling wine can be made like 7-Up is made, by injecting carbon dioxide into white wine. It’s called the charmat method, and it’s the cheapest way to make sparkling wine. In these wines you’ll see giant bubbles just like in a glass of soda. Most Italian Prosecco, unless the bottle says otherwise, is made using the charmat method.

The vast majority of Cava, however, is made using método tradicional (méthode champenoise in Champagne and méthode traditionnelle elsewhere in France). Typically, the finer the tine, the tinier the bubbles.

THE TRADITIONAL METHOD, IN A NUTSHELL

Harvest: The grapes are generally harvested young, with higher acid and less sugar. They are crushed and fermented as still wines. Once fermentation is complete, they are bottled with a dose of sugar, and yeast called Liqueur de tirage.

En tirage: This is the period of aging that creates the bubbles by reactivating the fermentation for a second time (secondary fermentation) in the bottle. Once the secondary fermentation is complete, the yeast dies and settles on the bottom of the bottle. This is called lees.

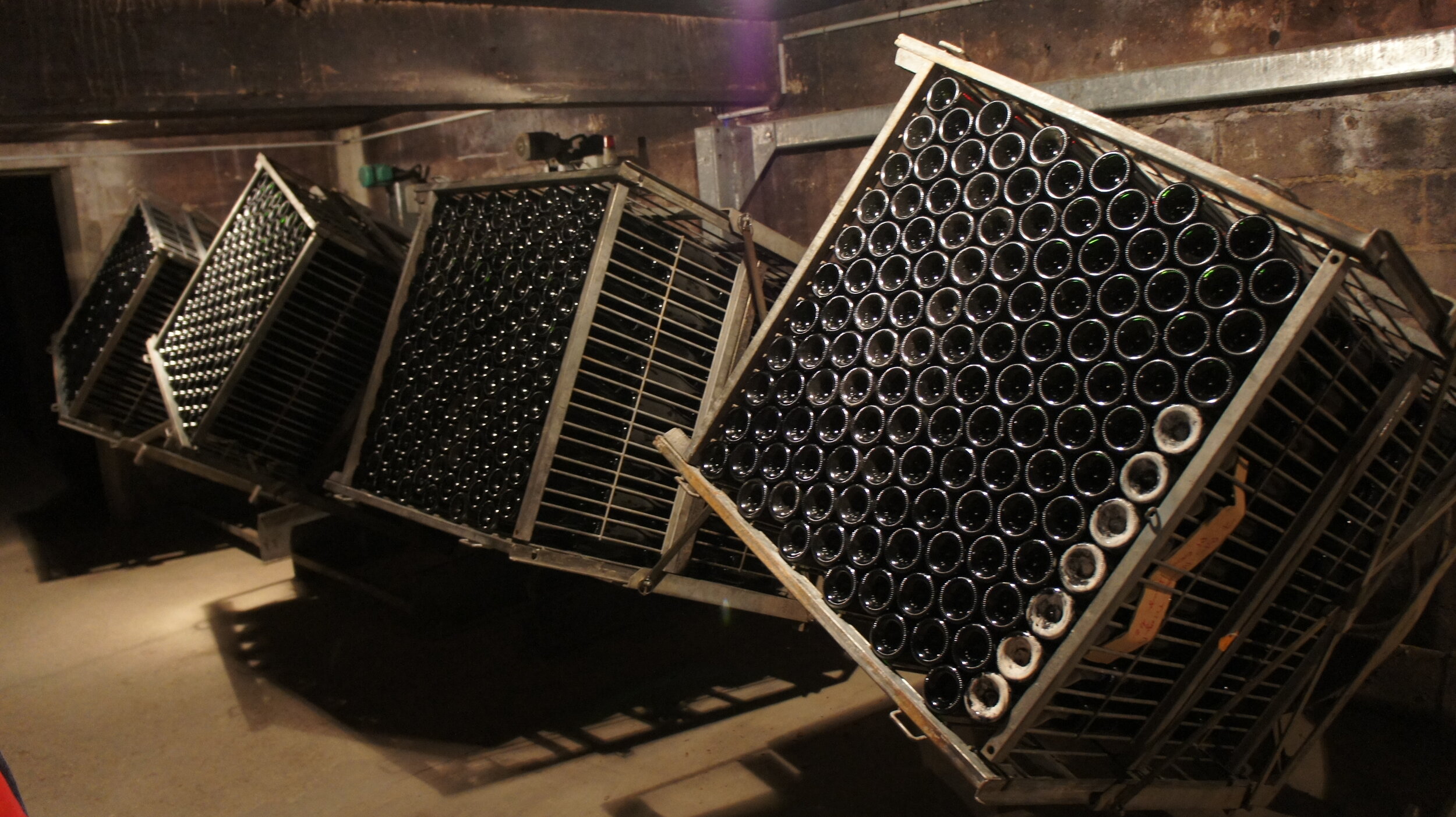

Aging on the lees: This is the time the wine is simply left alone in a dark cool place, preferably in underground cellars or caves. Once the wine has aged on its lees based on the winemaker’s preference, it’s time to riddle.

Riddling/Remuage: This is the process where cellar workers would give each bottle (facing neck down, at a 45 degree angle) a quarter turn twist once a day. With each twist the bottle moves into a more upright position with the neck facing down. This causes the lees sediment to work its way gently down toward the temporary cap. Once the wine has fully aged on its lees and the sediment has been riddled down into the neck of the bottle, it’s time for disgorgement.

Disgorging: The bottle necks are flash frozen in what is called a cooling bath. The cooling temp is around -27C. The sediment now frozen, is like a plug. The temporary cap is removed and the pressure from the bubbles forces the plug to shoot out of the bottle. The bottle is then finished with dosage.

Dosage: The final step of the process. After the plug of sediment is removed, a dose of wine is used to top off the bottle. Sometimes the dose is sweetened and for the driest wines like those designated Brut or Nature, no sugar is generally added. The wine is then corked with the traditional sparkling wine cork and the wire cage is applied to keep the cork from popping out with the added bubble pressure.

HOW NOT TO LOSE AN EYE IN THE CAVE

In the earliest days, a poor fool tasked with riddling bottles of wine that suffer ever-increasing pressure might lose an eye when a bottle exploded. Today the bottles are stronger (the punt, or large thimble-shaped formation at the bottom of the bottle makes it stronger). Also, the Catalans—not the French!—invented the modern riddling technology, in which a machine does the turning of each bottle every day. Some producers claim to continue to riddle by hand (it makes no difference in quality if it’s done correctly), but one small Cava producer we visited actually does it by hand even today. It’s labor intensive, as you might imagine.

The device the Catalans invented is called a girasol (“sunflower”) in Spanish; gyropalette in French. It holds about 60 bottles, and the entire cage can be moved slightly every day to move the sediment into the neck, mechanically. This process have cut down on the extreme labor time needed to do the job one bottle at a time by hand—and probably saved a lot of carpal tunnel syndrome problems along the way. Not to mention, an eye.

More photography from the wine caves!

The caves are in some cases many stories underground. It stays naturally cool down there. With light, you can see the sediment in the bottles. Also pictured is the handheld device that hooks to a wire and produces light, rather than wiring the entire cave with light switches.

HOW IS QUALITY JUDGED?

Officially, Spain has a very rigorous grading system for their designated wines. First, all Cava wines must be aged a minimum of 9 months on their lees. From here, there are three levels of quality based on bottle aging.

Crianza — with the minimum of 9 months bottle aging before release

Reserva — at least 15 months on the lees before release

Gran Reserva — at least 30 months — but some of the finer Cavas are aged much longer than the minimum

It’s not only about time. If the wine presented to the commission for designation doesn’t pass muster based on a rigorous list of criteria, the wine isn’t allowed to list the quality level it was hoping for. Over 50% of the Gran Reserva is awarded to just one Cava house. You will read about that later.

Generally speaking, with sparkling wines, the finest are dry, with an essence of yeast. Think fine, fresh baked brioche. The bubbles are minuscule. Here is a guide to sweetness in sparkling wine:

Brut Nature — also called “Natural” in California sparkling wine — these are bone dry. It’s our favorite Cava. It contains less than half a gram of sugar per glass.

Brut

Extra Brut

Extra Dry

Dry

Demi Sec — the sweetest sparkling wines contain over 8 grams of sugar per glass

Yes, we were really there.

WHAT IS THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE FOR CAVA MAKERS?

Here’s the challenge, mostly for Spain, but for us as wine lovers as well.

Cava, like most Spanish wines, is generally considered a bargain wine. When thinking about some casual bubbles for a pool party, we may stock up on inexpensive bottles of Cava or Prosecco, but when it’s time to splurge for a major celebration we turn back to French Champagne.

Baby vines on a hill overlooking the valley, with Montserrat in the distance. Barcelona lies to the right, out of the photograph. The view is north.

Some years ago, Spain decided to break into the very lucrative American wine market. At the time, Spanish wine was not considered sophisticated, so the Catalans decided to make the wine affordable, hoping people would discover the wine, gobble it up, and drive up the price. But the price did not go up, because the region never marketed itself and never gained an identity. Chile has the same problem, and its wines are similarly undervalued more often than not.

Compounding the problem was that large producers in Penedès became adept at using economies of scale to produce massive quantities of Cava, and though they have profited, the price of the wine remains low in part because it’s so plentiful. It’s now considered by many to be roughly synoymous with Prosecco—when much of it is better.

The challenge facing Penedès is this: how to increase the prestige of the region? To answer this, we need to know the history of the region.

WHAT IS CAVA’S HISTORY?

Cava production in Spain began late compared to Champagne.

Penedès, near Barcelona, is the Spanish DO (Denominación de Origen, designation of origin) that produces 95% of Spain’s Cava wines. Unlike Champagne, France, Cava can be used on any Spanish sparkling wine label. The word translates “cellar” or “cave.”

Although attempts to make sparkling wines had been going on for ages in Spain, the first truly successful sparkling wine was introduced to the market in 1879, with six original bottles sold.

It all started in 1872 with a group of winemaking friends from Penedès called the Seven Sages. Joseph Raventós i Fatjó was the leader of the group and the head winemaker for his family bodega (winery), Codorníu. Codorníu is still one of the most known Cava houses in the world.

Though the French dismissively consider Cava to be universally inferior to most sparkling French wines, the French were in fact instrumental in the success of Cava-making, with many Penedès Cava houses consulting French oenologists in the early stages of their development. Since Penedès lies in Catalunya. the Catalans originally wanted to call their sparkling wine Xampán (Catalan for Champagne).

Of course the French protested loudly. You may know that sparkling wine cannot be called “Champagne” unless the grapes are grown in the Champagne wine region—a great example of marketing and proprietorship on the part of these French winemakers.

From nearer the valley floor looking north.

In Penedès, despite the protests from the French, the Spanish called their wines Spanish Champagne or Xampán for many years. France forced this to stop in 1986 when Spain joined the EEC (European Economic Community, an economic arrangement predating the EU). From there, the name “Cava” took over, but Penedès did not think to take ownership of the name, and now any Spanish winery is allowed to call their sparkling wine “Cava.”

TRIVIA MOMENT: Penedès can be noted as one of France’s Champagne saviors when the terrible vine-destroying disease Phylloxera almost destroyed the entire French wine industry. Penedès grape farmers quickly started planting vineyards and developed an export market delivering desperately needed fruit to France until they could reestablish their famed vineyards in Champagne.

THE DEBATE

Today, due to the fact that 95% of all Cava is made in Penedès, the Catalans would prefer the name be specific to their region, but the “Penedès” DO is used only for inexpensive still table wines. If “Cava” is on the label, the producers can’t say “Penedès.”

Today many of the Cava houses in Pendes are rallying together to gain more autonomy, and a new name is growing in popularity - Classic Penedès.

The marketing strategy of Albet i Noya (2020). Notice “Classic Penedès.”

Many of the smaller, more innovative wineries are starting to use this designation and not “Cava” on their labels. It could prove a challenge in the export market, with so many consumers familiar with Cava as the sparkling wine name of Spain, but for us as wine writers and wine educators, the idea is brilliant and should pay off with huge identity dividends once more Penedès houses use the name.

Many of the larger Cava houses are less enthusiastic about the change. They’d rather work with the Spanish wine council and get the name Cava designated for Penedès alone. The end result is still unknown.

HOW AMAZING CAN CAVA BE?

Cavas from Penedès are some of the most amazing sparkling wines in the world. They rival France in quality, and yet at the moment sell for a fraction of the cost.

One thing many Penedès Cava houses pride themselves with, is going far beyond the required 9 - 30 months aging on the lees. The higher quality versions are often left alone for years, some up to 10. These long-aged wines offer amazing smoothness and complexity the younger wines simply can’t achieve.

As the Spanish put it, the aged wines are softer, the bubbles less gassy and hard. Younger Cava wines, as with any young sparkling wines, can be more active and bubbly, but also more aggressive and gassy. Some high-end Cava wines are extremely smooth, soft, and the bubbles are tiny and gentle.

The best sparkling wine Jake has yet had in his wine education, and Patrick agrees it’s one of the best sparkling wines in the world, is Cava Guilera’s Gran Reserva 2006 Brut Nature Agosarat, aged 13 years between harvest and disgorgement about 6 weeks before our visit. For those who are bad at math, that’s around 150 months.

Read about the different Penedès wineries we visited, ranging from huge to family-owned and tiny, and some that focus primarily on still wines.

Juvé y Champs - The Cava royalty marvel — COMING SOON

Cava Guilera - The Cava artist in action marvel — COMING SOON

Can Rafols - The ancient Roman road marvel — COMING SOON

Albet i Noya - The Biodynamic marvel — COMING SOON